HISTORY AND ORGANIZATION

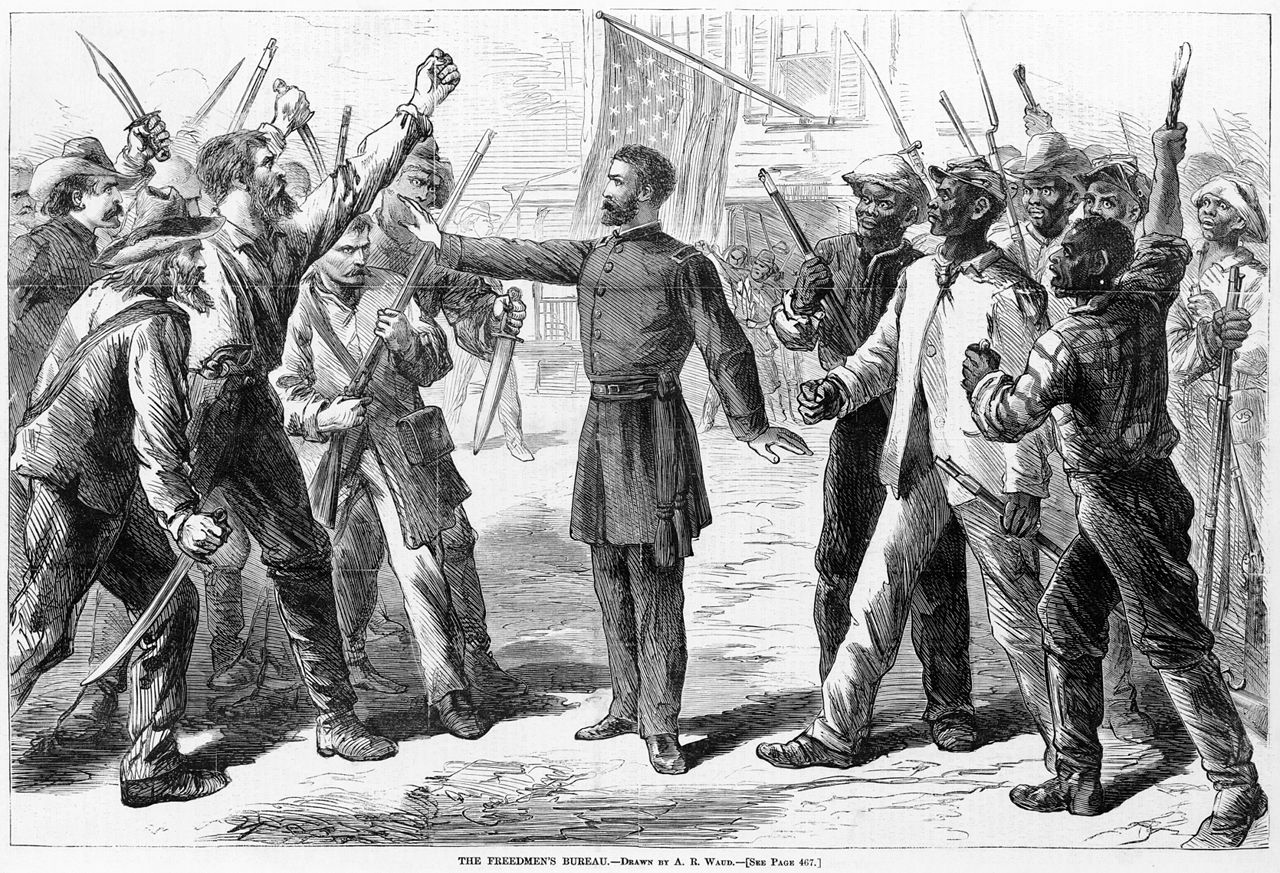

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, also known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was established in the War Department by an act of Congress on March 3, 1865 (13 Stat. 507). The life of the Bureau was extended twice by acts of July 16, 1866 (14 Stat. 173), and July 6, 1868 (15 Stat. 83). The Bureau was responsible for the supervision and management of all matters relating to refugees and freedmen, and of lands abandoned or seized during the Civil War. In May 1865, President Andrew Johnson appointed Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard as Commissioner of the Bureau, and Howard served in that position until June 30, 1872, when activities of the Bureau were terminated in accordance with an act of June 10, 1872 (17 Stat. 366).

While a major part of the Bureau’s early activities involved the supervision of abandoned and confiscated property, its mission was to provide relief and help freedmen become self-sufficient. Bureau officials issued rations and clothing, operated hospitals and refugee camps, and supervised labor contracts. In addition, the Bureau managed apprenticeship disputes and complaints, assisted benevolent societies in the establishment of schools, helped freedmen in legalizing marriages entered into during slavery, and provided transportation to refugees and freedmen who were attempting to reunite with their family or relocate to other parts of the country. The Bureau also helped black soldiers, sailors, and their heirs collect bounty claims, pensions, and back pay.

The act of March 3,1865, authorized the appointment of Assistant Commissioners to aid the Commissioner in supervising the work of the Bureau in the former Confederate states, the border states, and the District of Columbia. While the work performed by Assistant Commissioners in each state was similar, the organizational structure of staff officers varied from state to state. At various times, the staff could consist of a superintendent of education, an assistant adjutant general, an assistant inspector general, a disbursing officer, a chief medical officer, a chief quartermaster, and a commissary of subsistence. Subordinate to these officers were the assistant superintendents, or subassistant commissioners as they later became known, who commanded the subdistricts.

The Assistant Commissioner corresponded extensively with both his superior in the Washington Bureau headquarters and his subordinate officers in the subdistricts. Based upon reports submitted to him by the subassistant commissioners and other subordinate staff officers, he prepared reports that he sent to the Commissioner concerning Bureau activities in areas under his jurisdiction. The Assistant Commissioner also received letters from freedmen, local white citizens, state officials, and other non-Bureau personnel. These letters varied in nature from complaints to applications for jobs in the Bureau. Because the assistant adjutant general handled much of the mail for the Assistant Commissioner’s office, it was often addressed to him instead of to the Assistant Commissioner.

In a circular issued by Commissioner Howard in July 1865, the Assistant Commissioners were instructed to designate one officer in each state to serve as “general Superintendents of Schools.” These officials were to “take cognizance of all that is being done to educate refugees and freedmen, secure proper protection to schools and teachers, promote method and efficiency, correspond with the benevolent agencies which are supplying his field, and aid the Assistant Commissioner in making his required reports.” In October 1865, a degree of centralized control was established over Bureau educational activities in the states when Rev. John W. Alvord was appointed Inspector of Finances and Schools. In January 1867, Alvord was divested of his financial responsibilities, and he was appointed General Superintendent of Education.An act of Congress, approved July 25, 1868 (15 Stat. 193), ordered that the Commissioner of the Bureau “shall, on the first day of January next, cause the said bureau to be withdrawn from the several States within which said bureau has acted and its operation shall be discontinued.”

Consequently, in early 1869, with the exception of the superintendents of education and the claims agents, the Assistant Commissioners and their subordinate officers were withdrawn from the states.For the next year and a half the Bureau continued to pursue its education work and to process claims. In the summer of 1870, the superintendents of education were withdrawn from the states, and the headquarters staff was greatly reduced. From that time until the Bureau was abolished by an act of Congress, effective June 30, 1872, the Bureau’s functions related almost exclusively to the disposition of claims. The Bureau’s records and remaining functions were then transferred to the Freedmen’s Branch in the office of the Adjutant General. The records of this branch are among the Bureau’s files.

THE FREEDMEN’S BUREAU IN MARYLAND AND DELAWARE ORGANIZATION

In June 1865, Comm. Oliver Otis Howard appointed Col. John Eaton as the Assistant Commissioner of the District of Columbia, which included Maryland, the District, the city of Alexandria, and the neighboring Virginia counties of Fairfax and Loudon. On September 27, 1865 (Special Order Number 77), Commissioner Howard appointed Lt. Col. William P. Wilson as acting Assistant Superintendent for Maryland. Wilson served until March 30, 1866, and was then replaced by Bvt. Maj. Gen. George J. Stannard, who became the first Assistant Commissioner for Maryland. Stannard’s headquarters was at Baltimore. His command included all of the state, except the counties of Calvert, Charles, Montgomery, Prince Georges, and St. Marys, which were under the control of the Assistant Commissioner of the District of Columbia. In early summer 1866, six counties in Virginia and two in West Virginia, known as the Shenandoah Division, were added to the Maryland Command (transferred to the Virginia command in the following September). By July 1866, Bvt Maj. Gen. Francis Fessenden replaced Stannard, and served for 1 month before he was replaced by Bvt. Maj. Gen. Edgar M. Gregory. On January 16, 1867 (Special Order Number 7), Maryland’s jurisdiction was expanded to include Delaware. Bvt. Brig. Gen. Horace M. Brooks replaced Gregory in January 1868, and by August 1868, Bureau affairs relating to Maryland and Delaware were reassigned to the Assistant Commissioner for the District of Columbia. A subassistant commissioner, Fred C. Von Schirach, remained in Baltimore until December 1868. A claims agent remained in Baltimore until 1872.

ACTIVITIES

Unlike its operations in states of the Deep South where providing relief, supervising labor contracts, and the administration of abandoned property was of primary concern, the Bureau’s activities in Maryland and Delaware and other areas under its jurisdiction centered largely on freedmen education, the administration of justice, and veterans’ claims.The Freedmen’s Bureau’s efforts to provide education for freedmen in Maryland was hampered by a system of illegal apprenticeship of school-age children. In direct conflict with the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (14 Stat. 27), black children were being bound to their former owners for indefinite periods of time with the help of Maryland government officials. An estimated 10,000 black children were bound out as apprentices between 1864 and 1867. The Bureau, however, through writs of habeas corpus and other court actions, fought vigorously to have these children released. By 1868, the intense efforts of the Bureau had largely ended the apprenticeship system in Maryland.

1 Although the illegal apprenticeship system hindered the Bureau’s educational activities in Maryland, the agency still managed to provide assistance with the construction and repair of school buildings and protection of and transportation for teachers. To increase its visibility and to gauge the interest of freedmen in establishing schools, Maryland and District of Columbia Bureau officials traveled to various counties, holding meetings on the benefits of education and the agency’s intention to provide aid for schools. In addition, the Bureau worked closely with private benevolent societies, such as the Baltimore Association, the American Missionary Association, and the Freedmen’s Union Association, to sustain freedmen schools in spite of intense and often violent opposition from whites. From October 1867 to October 1868, the Bureau provided aid and assistance to some 80 schools in Maryland.

2 Although the black population in Delaware and West Virginia was small, and Bureau operations in these states were limited, the agency still managed to provide noteworthy assistance for freedmen education. In Delaware the Bureau assisted in the construction of several freedmen schools. The agency also provided aid to various civic groups and benevolent societies, especially the Delaware Association for the Moral Improvement and Education of the Colored Race, which maintained some 23 schools in various parts of the state. West Virginia maintained a system of free education. However, whites controlled funds for schools and employment of teachers, and schools for blacks and whites remained separate, as required by law. Bureau officials, nonetheless, worked closely with the West Virginia superintendent of free schools in the establishment of schools for freedmen. As in Maryland, Bureau officials traveled throughout West Virginia counties, advising freedmen of their support and plans for building schools. Similar to other areas under its jurisdiction, the Bureau supplied funds for buildings, and teachers were generally paid from public funds, contributions from blacks, and aid from benevolent societies. By 1868, with cooperation mostly from freedmen themselves, the Bureau was able to establish 9 schools in West Virginia.

3 Safeguarding rights and securing justice for freedmen was of paramount concern to the Freedmen’s Bureau. Following the Civil War, several Southern states enacted a series of laws commonly known as “black codes,” which restricted the rights and legal status of freedmen. Freedmen were often given harsh sentences for petty crimes and in some instances were unable to get their cases heard in state courts. In a circular issued by Commissioner Howard on May 30, 1865, Assistant Commissioners were authorized, in places where civil law had been interrupted and blacks’ rights to justice were being denied, to adjudicate cases between blacks themselves and between blacks and whites. In the District of Columbia and Maryland, the civil process of law had not been interrupted, and unlike many areas of the South under the Bureau’s jurisdiction, no freedmen’s or provost courts were in operation. The Bureau did however, provide legal assistance to freedmen in civil and criminal cases in both the District of Columbia and Maryland. This was done especially in instances where freedmen lacked counsel and in cases where Bureau officials felt that freedmen were wrongly convicted or imprisoned. In 1868, the Assistant Commissioner for the District reported that of the nearly 900 cases handled by his office, a large percentage involved incidents in Maryland.

4 In accordance with a law passed by Congress on March 29, 1867 (15 Stat. 26), making the Freedmen’s Bureau the sole agent for payment of claims of black veterans, Bureau disbursing officers assisted veterans and their heirs in the preparation and settlement of claims. To administer claims, the Bureau established a Claims Division. This office was abolished in 1868, and most of the activities of the Maryland Bureau relating to claims were then centered in Baltimore, MD, where two full-time disbursing officers were assigned to settle and pay veterans claims. At the Baltimore office, the Bureau handled claims for Maryland, Delaware, and other areas under its jurisdiction. In 1868 Bureau agents disbursed more than $10,000 for military claims.5 The Bureau maintained registers and files for claimants for payments of bounty, back pay, and pensions. These records often contain the name, rank, company, and regiment of the claimant; the dates the claim was received and filed; the address of the claimant; and remarks.

ENDNOTES

1 Annual Reports of the Assistant Commissioners, District of Columbia, October 10, 1867, [pp. 3 – 9], Records of the Commissioner, Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, Record Group (RG) 105, National Archives Building; W. A. Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau in the Border States,” in Radicalism, Racism, and Party Realignment: The Border States during Reconstruction, ed. Richard O. Curry, (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1869), 247.

2 W. A. Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau in the Border States,” pp. 247 – 49. Annual Reports of the Assistant Commissioners, District of Columbia, October 10, 1868 [pp. 11 – 13, 15 – 24].

3 Annual Reports, Assistant Commissioners, District of Columbia, October 10, 1868, [pp. 26 – 30]. See also W. A. Low, “The Freedmen’s Bureau in the Border States,” 256 – 57.

4 Senate Ex. Doc. No. 6, 39th Cong., 2nd Sess., Serial Vol. 1276, p. 34; Annual Reports, Assistant Commissioners, District of Columbia, October 10, 1867 [p. 3], and October 10, 1868 [pp. 5 – 11].5 Annual Reports, Assistant Commissioners, District of Columbia, October 10, 1867 [pp. 10 – 11, and October 10, 1868 [pp. 13 – 15].