In the fall of 2019 I was surveying sources at the Maryland State Archives Hall of Records in Annapolis when I observed Prof. Ezra Greenspan at work on research on the records of Aaron Anthony, and his son John P. Anthony, as concerns Stephen Henry Bailey (1820 – 1894, USCT) 1st cousin to Frederick Bailey Douglass, and Perry Bailey (1814 – 1880), older brother to Frederick Bailey Douglass.

As Prof. Greenspan reviewed records of the Lloyd family, I remarked that the state of Maryland tells a lifeless and incomplete nursery rhyme story of the vastness and intricacy of its antebellum history of the Underground Railroad and Reconstruction with its repetitive rhetoric on Douglass, Tubman and others who have appeared on the covers of state publications for decades.

Specifically, I mentioned there should be a publication or effort to identify within the various regions of Maryland those that left the state to make significant and consequential contributions elsewhere, such as the AME ministers from Maryland that founded the AME church in the state of Florida.

In response to my riff, Greenspan remarked it was a measurable and significant step forward in his lifetime for Maryland, as well as the overall country, to begin to recognize Douglass and Tubman prominently with statues and artifices of state propaganda.

I can accept Prof. Greenspan’s observations for what it’s worth. As an elder, he has seen a slow acceptance and inclusion of Douglass and Tubman in our larger historical narrative. Yet as 2020 finally fades there is an imperative to uplift and advance the lost history once and forever or let us be damned in historical ignorance and apathy forever.

For example, the existing Network to Freedom infrastructure within the state of Maryland which includes 80 / 85 or so sites (many being unrelated to the UGRR such as the Howard County Historical Society’s location at the Miller Branch of the Howard County Library) is incredibly incomplete and inconsistent.

Lost History Associates has 50 stories that remain untold, with another 50 after that, and yet again another 50 stories, tales, narratives and histories the WGM and the apathetic state historical / tourism industrial complex could not care less about.

Therefore … we give you a lost history on the house.

Raise your lighters up in the midnight hour for the lost history.

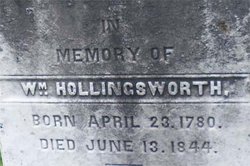

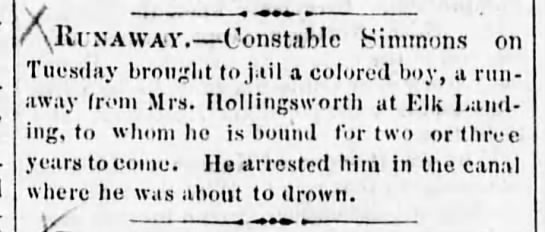

I, JOHN THOMAS, was born in Elkton, Cecil county, Maryland, April 1st, A. D. 1825, in the house of my master, William Hollingsworth, being born a slave. I remained with him until I was thirteen years of age, when I took one of his blooded mares and made my escape.

Whilst riding, I met a number of men, one of whom said to me: “Little boy, where are you going?” “I am going to Mr. Cuche’s mill.”

“Who do you belong to?” “I belong to Mr. William Hollingsworth.”

I, at the time, had on two pairs of pants, with leather suspenders over my coat. A man asked me, “Why do you wear your suspenders over your coat?” “These are my overalls, to keep my pants clean.”

Ere I arrived at Mr. Cuche’s mill, I met a little boy. I said to him, “Little boy, what is the name of the next town beyond Mr. Cuche’s mill?”

He told me, “New London Cross Roads.”

Ere I arrived there I met a white man. He accosted me thus: “Boy, who do you belong to?” I told him that I belonged to Mr. William Hollingsworth.

“Where are you going to now?” “I am going to New London.”

At New London I met a school-boy. I asked him, “Where is the line that divides Maryland from Pennsylvania?” He said, “New London is the line.” I asked him, “What is the name of the next town?” He said, “Eaton Town.”

On my way I met another man; he said to me, “Where are you going?” I answered, “To Eaton Town.”

He said, “Where are you from?” I said, “Cuche’s Mill.” He asked me if I belonged to Mr. Cuche? I said, “Yes.”

On my way I met two more men. They asked the same questions. I answered as before.

When I arrived at Eaton Town I asked a little boy what the name of the next town was. He said, “Russelville.”

As I went I saw a colored man cutting wood in the woods. I asked him, “What was the name of the next town?”

He said, “Russelville.” I asked him if any colored families lived there? He said, “Yes; Uncle Sammy Glasgow.” He advised me to stop there. He asked me where I belonged. I said, “In New London Cross Roads.” And for fear that he would ask to whom I belonged, I whipped up my house and went my way.

I was then a few miles in Pennsylvania, and I felt that I was a free boy and in a free State. I met a man, and he asked me where I was going? I said “Russelville, to Uncle Sammy Glasgow.”

He asked me if I was a free boy. I said, “Yes.” He said “You look more like one of those little runaway niggers than anything else that I know of.” I said, “Well, if you think I am a runaway, you had better stop me, but I think you will soon let me go.”

I then went to Russelville, and asked for Sammy Glasgow, and a noble old gentleman came to the door, and I asked him if he could tell me the way to Somerset, and he pointed out the way. I asked him if he knew any colored families there.

He said, “Yes.” He told me of one William Jourden, the first house that I came to, on my left hand. This Jourden was my stepfather; he married my mother, who had runaway years before, and the way that I knew where she lived was through a man by the name of Jim Ham, who was driving a team in Lancaster City, whose home was in Elkton.

He came home on a visit, and was talking to one of the slave women one night; he sat with his arm around her, I, a little boy, sitting in the chimney corner asleep, as they thought, but with one eye open and alistening.

He whispered to her, saying, “I saw that boy’s mother.” She said, “Did you? Where?”

He said, “In Somerset; she is married and doing well; she married a man by the name of William Jourden.” When I arrived at my mother’s house, I met my stepfather in the yard cutting wood, and I asked him if Mrs. Jourden was at home? He said, “Yes;” and asked me in.

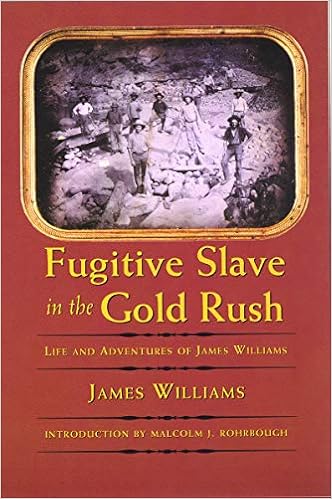

I went in and sat down by the door. My mother asked me my name. I answered, “James Williams.” She said. “Come to the fire and warm yourself!” I said, “No; that I was not cold.” After sitting there awhile, I asked her if she had any children.

She said, “Yes;” and named one boy that belonged to William Hollingsworth, in Elkton.

I asked if she had any more. She named my sister that belonged to Thomas Moore, of Elkton, Vic, that had run away and was betrayed by a colored man, for the sum of one hundred dollars.

I had a brother that went with my mother when she run away from Maryland. She did not say anything about him, but spoke of John Thomas. I asked her if she would know him if she saw him.

She said, “Yes.” I said, “Are you sure that you would know him?” She answered, “Yes; don’t you think I would know my own child?” And becoming somewhat excited, she told me that I had a great deal of impudence; and her loud tone brought her husband in, and he suspicioned me of being a spy for the kidnappers.

He came with a stick and stood by the door, when an old lady, by the name of Hannah Brown, exclaimed: “Aunt Abby, don’t you know your own child? Bless God, that is him.”

Then my mother came and greeted me, and my father also. My mother cried, “My God, my son, what are you doing here?” I said, “that I had given leg-bail for security.” My father took the horse and hid it in the fodder stack. That night, one William Smith; who was a good old minister, went back on the road, about six miles, with the horse, and put her on the straight road, and started her for home; but the bridle he cut up and threw into a mill race. I was told that on the morning of the second day the horse stood at her master’s gate.

To show the reader how my mother got free, I shall have to digress a little.

She was sold by Tom Moore to Mr. Hollingsworth, for a term of two years, for the sum of one hundred dollars, and at the expiration of that time, she was to go back to Tom Moore’s.

One morning Mr. Hollingsworth said, “Abby, it is hard enough to serve two masters, and worse to serve three. You have got three months to serve me yet, but, here is twenty-five dollars; I won’t tell you to run away. You can do as you like.” He told my uncle Frisby to take the horse and cart and carry her as far as a brook, called Dogwood Run, on the way to Pennsylvania.

By these means my mother got her freedom, which shows that Hollings-worth had a Christian spirit, though a slaveholder. I stayed one night at my mother’s, and in the morning I was taken on the underground railroad, and they carried me to one Asa Walton, who lived at Penningtonville, Pennsylvania, and he took me on one of his fastest horses and carried me to one Daniel Givens, a good old abolitionist, who lived near Lancaster City; and I travelled onward from one to another, on the underground railroad, until I got to a place of refuge.

This way of travel was called the Underground Railroad.

At the age of sixteen I commenced my labors with the underground road. The way that we used to conduct the business was this: a white man would carry a certain number of slaves for a certain amount, and if they did not all have money, then those that had had to raise the sum that was required.

We used to communicate with each other in this wise: one of us would go to the slaves and find out how many wanted to go, and then we would inform the party who was to take them, and some favorable night they would meet us out in the woods; we would then blow a whistle, and the man in waiting would answer “all right;” he would then take his load and travel by night, until he got into a free State.

Then I have taken a covered wagon, with as many as fourteen in, and if I met any one that asked me where I was going, I told them that I was going to market. I became so daring, that I went within twenty miles of Elkton. At one time the kidnappers were within one mile of me; I turned the corner of a house, and went into some bushes, and that was the last they saw of me.

The way we abolitionists had of doing our business was called the underground railroad.

Notes:

Elk Landing – Find Your Chesapeake